Solving an optimization problem is not a linear process, but the process can be broken down into five general steps:

- Getting the problem description

- Formulating the mathematical program

- Solving the mathematical program

- Performing some post-optimal analysis

- Presenting the solution and analysis

However, there are often “feedback loops” within this process. For example, after formulating and solving an optimization problem, you will often want to consider the validity of your solution (often consulting with the person who provided the problem description). If your solution is invalid you may need to alter or update your formulation to incorporate your new understanding of the actual problem. This process is shown in the Operations Research Methodology Diagram.

The modeling process starts with a well-defined model description, then uses mathematics to formulate a mathematical program. Next, the modeler enters the mathematical program into some solver software, e.g., Excel and solves the model. Finally, the solution is translated into a decision in terms of the original model description.

Using Python gives you a “shortcut” through the modeling process. By formulating the mathematical program in Python you have already put it into a form that can be used easily by PuLP the modeller to call many solvers, e.g. CPLEX, COIN, gurobi so you don’t need to enter the mathematical program into the solver software. However, you usually don’t put any “hard” numbers into your formulation, instead you “populate” your model using data files, so there is some work involved in creating the appropriate data file. The advantage of using data files is that the same model may used many times with different data sets.

The Modeling Process

The modeling process is a “neat and tidy” simplification of the optimisation process. Let’s consider the five steps of the optimisation process in more detail:

Getting the Problem Description

The aim of this step is to come up with a formal, rigourous model description. Usually you start an optimisation project with an abstract description of a problem and some data. Often you need to spend some time talking with the person providing the problem (usually known as the client). By talking with the client and considering the data available you can come up with the more rigourous model description you are used to. Sometimes not all the data will be relevant or you will need to ask the client if they can provide some other data. Sometimes the limitations of the available data may change your model description and subsequent formulation significantly.

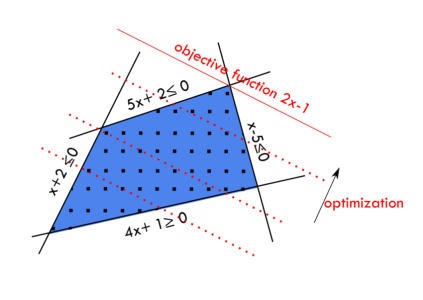

Formulating the mathematical program

In this step we identify the key quantifiable decisions, restrictions and goals from the problem description, and capture their interdependencies in a mathematical model. We can break the formulation process into 4 key steps:

- Identify the Decision Variables paying particular attention to units (for example: we need to decide how many hours per week each process will run for).

- Formulate the Objective Function using the decision variables, we can construct a minimise or maximise objective function. The objective function typically reflects the total cost, or total profit, for a given value of the decision variables.

- Formulate the Constraints, either logical (for example, we cannot work for a negative number of hours), or explicit to the problem description. Again, the constraints are expressed in terms of the decision variables.

- Identify the Data needed for the objective function and constraints. To solve your mathematical program you will need to have some “hard numbers” as variable bounds and/or variable coefficients in your objective function and/or constraints.

Solving the mathematical program

For relatively simple or well understood problems the mathematical model can often be solved to optimality (i.e., the best possible solution is identified). This is done using algorithms such as the Revised Simplex Method or Interior Point Methods. However, many industrial problems would take too long to solve to optimality using these techniques, and so are solved using heuristic methods which do not guarantee optimality.

Performing some post-optimal analysis

Often there is uncertainty in the problem description (either with the accuracy of the data provided, or with the value(s) of data in the future). In this situation the robustness of our solution can be examined by performing post-optimal analysis. This involves identifying how the optimal solution would change under various changes to the formulation (for example, what would be the effect of a given cost increasing, or a particular machine failing?). This sort of analysis can also be useful for making tactical or strategic decisions (for example, if we invested in opening another factory, what effect would this have on our revenue?).

Another important consideration in this step (and the next) is the validation of the mathematical program’s solution. You should carefully consider what the solution’s variable values mean in terms of the original problem description. Make sure they make sense to you and, more importantly, your client (which is why the next step, presenting the solution and analysis is important).

Presenting the solution and analysis

A crucial step in the optimisation process is the presentation of the solution and any post-optimal analysis. The translation from a mathematical program’s solution back into a concise and comprehensible summary is as important as the translation from the problem description into the mathematical program. Key observations and decisions generated via optimisation must be presented in an easily understandable way for the client or project stakeholders.

Your presentation is a crucial first step in the implementation of the decisions generated by your mathematical program. If the decisions and their consequences (often determined by the mathematical program constraints) are not presented clearly and intelligently your optimal decision will never be used.

This step is also your chance to suggest other work in the future. This could include:

- Periodic monitoring of the validity of your mathematical program;

- Further analysis of your solution, looking for other benefits for your client;

- Identification of future optimisation opportunities.