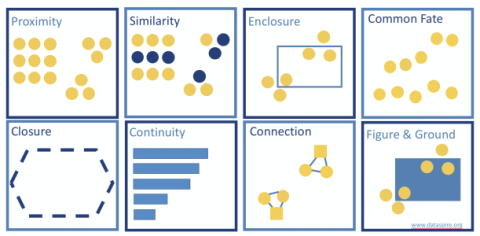

When we creating and communicating with data, one of the easiest way to leverage the principles of visual perception, those useful principles are:

PROXIMITY

The proximity principle identifies our tendency to perceive objects that are physically close to each other as belonging to part of the same group, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. For example, our eyes often connect the nine dots in the 3x3 box on the left together, the three dots in the upside-down triangle on the right together, and the three dots in the triangle on the bottom right together. Our eyes group these dots together before we even know what we are looking at in the dots.

SIMILARITY

The similarity principle outlines our tendency to perceive objects of similar color, shape, size, and/or orientation as related or belonging to part of the same group, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. For example, our eyes group the blue dots together and the yellow dots together as presuming that they have something in common with one another because of their shared color. We do this before we even know what the blue and yellow colors means.

ENCLOSURE

The enclosure principle reflects our tendency to perceive objects physically enclosed together in a ways that seems to create a boundary around that which is related or belonging to part of the same group, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. For example, our eyes see the yellow dots within the blue rectangle as having something in common with one another as they are all “in the box” together. We attribute meaning to the “box” whether that is accurate or not given what we are looking at.

CLOSURE

The closure principle points out our tendency to perceive a set of individual components as a single, recognizable shape whenever possible, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. Meaning rather than perceiving something as open and incomplete, we “fill in the space” to make things closed and complete. For example, our eyes connect the dashed lines to create a hexagon, rather than seeing the unusual nature of different dashes in space. They jump to these closed and complete shapes before we actually know what we are looking at often.

CONTINUITY

The continuity principle identifies our tendency to perceive objects that are in line with one another or seem to be a continuation of one another as part of a single whole or group, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. Our eyes search for the smoothest path to follow, thus looking for continuity among objects. For example, our brains presume that all of these blue bars share a common baseline, our eyes see that the left side of each bars aligns together. Also, our eyes perceive that the blue bars are decreasing as you go down and presume meaning to that.

CONNECTION

The connection principle points out our tendency to perceive objects that are physically connected are part of the same group, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. For example, our eyes connect the group of three shapes in the lower left together and the three shapes in the upper right together, before connecting the dots and squares together. In fact, the connection principle often is stronger than proximity or similarity principles, but not as strong as enclosure.

FIGURE & GROUND

The figure & ground principle outlines our tendency to perceive objects either in the foreground or in the background with the background having less implied meaning, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. Specifically, the figure is considered the object, shape, or person that is in focus of the visual field and where we “should” pay attention, and the ground is what is in the background and “should” be ignored. For example, our eyes perceive the yellow dots being “in front of” the blue rectangle and perceive that “in front of” quality as indicating more importance. We either ignore or downplay what is in the background, without knowing what is there.

COMMON FATE

The common fate principle reflects our tendency to perceive objects that share a direction of placement together, or seem to be moving together, as a unified group, whether or not that is true or relevant to the data at hand. For example, our eyes see the five top yellow dots from left to right as being a group increasing from left to right, and the bottom five dots as being a group staying the same from left to right. Before we know if the data are related, we begin to group these dots together in our mind